Chest, probably Columbia County, New York, 1775. Pine. H. 18 1/4 ", W. 52 1/2 ", D. 20". (Courtesy, New York State Museum, Albany, New York.)

Chest, Schoharie County, New York, 1778. Pine. H. 20 1/2 ", W. 47 1/2 ", D. 21 1/2 ". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art.)

Schränk, Dutchess or Ulster County, New York, 1715-1740, Maple with white pine and yellow pine. H. 83 1/4", W. 76 3/4", D. 29". (Courtesy, Ulster County Historical Society; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

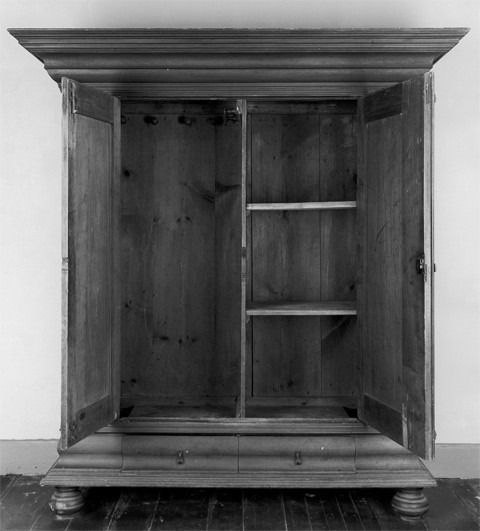

Schränk, Dutchess or Ulster County, New York, 1715-1740, Maple with white pine and yellow pine. H. 76", W. 76", D. 29 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The iron drawer pulls are replacements based on the originals on the schränk illustrated in fig. 3.

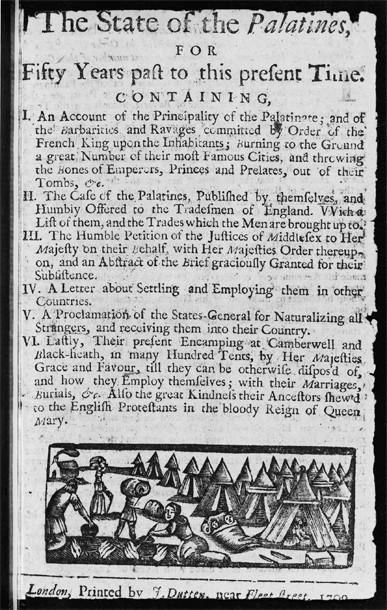

Title page from The State of the Palatines, For Fifty Years past to this present Time (1709) showing the Palatines soon after their arrival in England encamped outside London at Camberwell or Blackheath. (Courtesy, Houghton Library, Harvard University EC7.A100.709s2.)

Robert Hunter, attributed to Sir Godfrey Kneller, England, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Collection of the New-York Historical Society.)

Robert Livingston, attributed to Nehemiah Partridge, New York, 1718. Oil on canvas. 50" x 40". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The painting is inscribed "AETAT 64 1718."

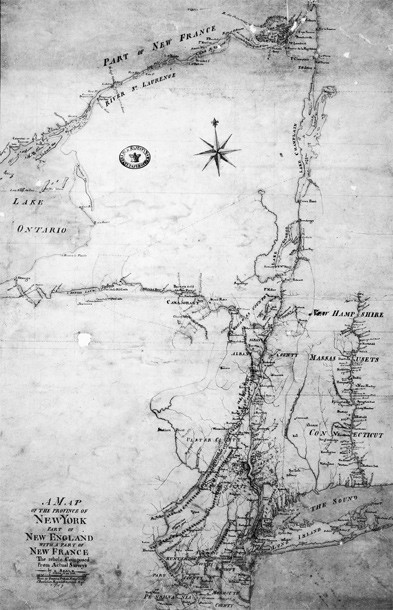

Frances Pfhister, A Map of the Province of New York, Part of New England, with Part of New France, 1759. (Courtesy, Public Records Office, London.) The area of detail shows Livingston Manor, East Camp, and Rhinebeck. The circles on the map indicate later Palatine settlements at Schoharie and Canajoharie.

Kast, possibly Rotterdam or Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1680-1690. Walnut veneer on oak. H. 90", W. 89 3/4", D. 31 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This elaborate Dutch baroque kast is one of seven owned in New Netherland and colonial New York. It descended in the family of Robert Livingston (fig. 7). His father, Rev. John Livingston (1603-1672), was a Scottish minister active in Scotland's struggle for independence from England. John was exiled to Rotterdam in 1663, where his son Robert was born, reared, and educated. Robert and his wife Alida Schuyler Van Rensselaer (1656-1727) may have purchased this kast after their marriage in 1679. Under the applied moldings on the right side panel is inscribed what appears to be the name "Myndert banta," possibly the maker, along with layout lines for cutting miters in the applied moldings.

Nasenschränk, Frankfurt, Germany, ca. 1700 (Copyright: Historisches Frankfurt/Main: Photographer: Horst Ziegenfusz.)

Interior view of the schränk illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Both of the horizontal shelves on the right side are modern, but the cleats for the original shelves are still in place. The schränk illustrated in fig. 4 was originally made with two full-width shelves. It is likely that the patron specified this arrangement since it represents a departure from the norm.

Kast, attributed to the Elting-Beekman shops, Kingston area of Ulster County, New York, 1700-1740. Red gum with white pine. H. 75 1/2", W. 73", D. 25 5/8". (Courtesy, Huguenot Historical Society of New Paltz; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the locking system on the schränk illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The large faceted end of the through-tenon and the thin wedge at the top lock the cornice substructure to the paneled side. The locking system on the schränk illustrated in fig. 4 is identical except the tenon is elliptical rather than faceted at the top. The individual components of the locking system are coded with the incised Roman numerals I-III and the Arabic numeral 4.

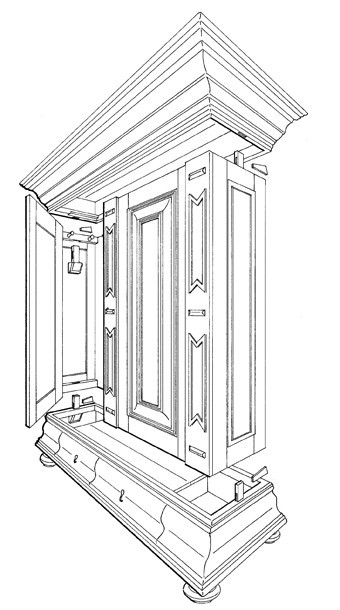

Isometric drawing of the schränk illustrated in fig 3. (Drawing by Dan Kershaw.)

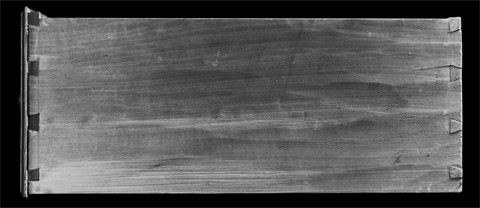

Detail of the drawer bottom of the schränk illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth). The drawer bottoms of the schränk illustrated in fig. 4 are secured with rosehead nails instead of wooden pins.

Details showing the (left) wedged dovetails of the schränk illustrated in fig. 4 and (right) unwedged dovetails of the one illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

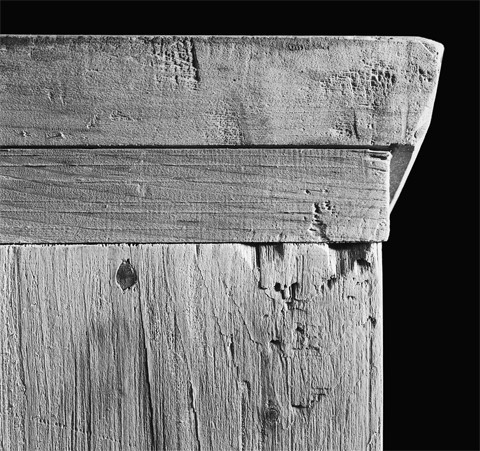

Detail of the cornice and architrave moldings on the schränk illustrated in fig. 3. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the cornice and architrave moldings on the schränk illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the foot and base molding on the schränk illustrated in fig. 3. The spline in the front corner has fallen out of the saw kerfs in the miter. The ebonized surface of the turned feet is original, and contrasts with the red-brown paint on the case. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the foot and base molding on the schränk illustrated in fig. 4. The original ebonized surface of the feet is visible under the later yellow ochre paint. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Wiäscheschränk, probably New York City, 1715-1740. Cherry with yellow poplar and red gum. H. 82 3/4", W. 78 1/2", D. 27". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The drawer handles are replaced. Filled holes and outlines from backplates on the drawer fronts suggest that they may have had baroque brass handles.

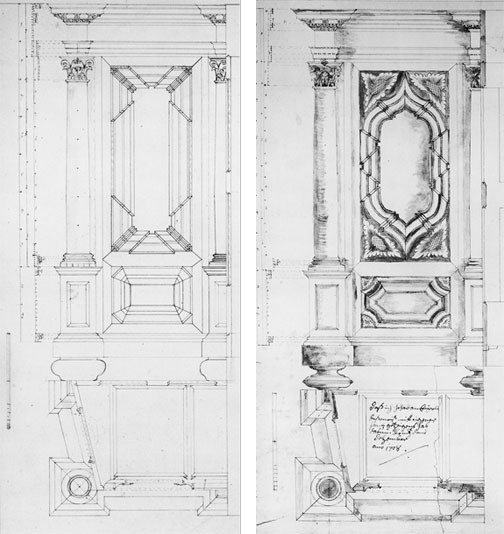

Drawings of schränke by (left) J. I. Frantzner and (right) J. A. Beyerle, Mainz, Germany. (Courtesy, Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.) The Frantzner drawing is dated 1697 and the Beyerle drawing is dated 1708.

Detail of a door panel of the wäscheschränk illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a drawer from the wäscheschränk illustrated in fig. 21. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Little is known about the material culture of the Germans who immigrated to New York from the Rhine River Valley, an area known as the Palatinate since its occupation by the Roman Empire. In the realm of furniture, only a small group of painted chests has been linked to this distinct ethnic group (figs. 1, 2). Most of these examples, however, represent the work of second-and third-generation descendants of the original Palatine settlers. Only a few are eighteenth century, and none are dated earlier than 1773. Thus, there is reason to celebrate the discovery of two eighteenth-century schränke made in the Hudson River Valley (figs. 3, 4). Even more exciting is the strong possibility that both of these quintessential German furniture forms are the products of a first-generation Palatine joiner in the vanguard of German settlers sent to New York in 1709/10.[1]

The first Palatines in New York arrived in 1708. Led by Rev. Joshua Kocherthal, a small party of forty-one settlers from Landau near Mannheim disembarked in New York City in December of that year and stayed on through the winter. The following year, the colonial governor made provisions for the Palatines to settle fifty-five miles north of the city on the western bank of the Hudson. There they established the settlement of Newburgh. Kocherthal received five hundred acres for a glebe plus an additional two hundred fifty acres for his family, whereas the heads of the other families received fifty acres each. Among this group of Palatines was a joiner who may have made both schränke.[2]

In immigrating to New York, Kocherthal's group preceded the mass exodus from the Rhine Valley that began in 1709. The Palatinate had been in an almost constant state of conflict from the onset of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) through the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). According to genealogist and historian Henry Z. Jones, Jr., the families of the New York immigrants had endured decades of suffering and dislocation as well as relentless taxation by whatever local prince had jurisdiction over their particular village or township. In his estimation the catalyst for the exodus was the severe winter of 1709. Throughout southern Germany, frigid temperatures ravaged crops, fruit trees, and vines thus destroying any hope for subsequent harvests. According to one observer, "the oldest people here could not remember a worse [cold]....Almost all mills have been brought to a standstill....Many cattle and humans,...even the birds and the wild animals in the woods froze." Enticed by British propaganda devised to lure settlers to the Crown's colonies in the New World, many Palatines began leaving their homeland the following spring. Most traveled up the Rhine to Rotterdam then on to London, where they were welcomed and sustained by the British government until plans could be made for their dispersal to the colonies.[3]

The massive scale of the Palatine exodus and the desperation, anxiety, and anticipation felt by many immigrants are reflected in the writings of Ulrich Simmendinger who left Germany in 1709. After spending several years in America, he returned home and published a brief account of the Palatine immigration and a register of the names and locations of the families that remained in New York. Simmendinger's account is both emotional and factual:

In the year 1709, when in consequence of the most golden promises of the English letters, many families departed from the Palatinate, and the districts of Zweibruecken, Hesse-Cassel, and also Waldeck, down the Rhine to England....As joyful as was the entrance upon our journey out of Wurtemburg, so sorrowful and sad the same suddenly became when in Rotterdam 1,000 souls were recalled and ordered back, the Queen having given new orders prohibiting the entrance of more immigrants. This pretext discouraged from their intended journey at that time more than 3,000 of the Catholic religion, who returned home rather than change faith at the demand of the Queen."[4]

Given the deteriorating and increasingly desperate social and economic conditions throughout southern Germany, it is hardly surprising that the Crown's propaganda campaign, which included the circulation of pamphlets that portrayed the American colonies as a land of unparalleled opportunity, proved to be so successful. During the spring and summer of 1709, nearly 13,000 Palatines arrived in London. To feed and house the immigrants, British officials distributed 1,600 tents and set up encampments at Blackheath, Greenwich, and Camberwell (fig. 5). Sickness and death stalked the crowded camps, and many of the weak, very young, and elderly died from fevers and contagious diseases. At first the Palatines were looked upon with a mixture of wonder and pity, but many poor Londoners became resentful and fearful that the immigrants would take their jobs and reduce wages. Although axe- and hammer-wielding mobs periodically attacked the encampments, the Palatines defended themselves vigorously. One early account describes an occasion when a small group of drunken Englishmen "made some [disparaging] Reflections upon the Receiving of these People into the Kingdom; which, being heard by one of the Palatines, he gave a hint to his Companions, and they all immediately came into the Room and beat the persons in a very rude and inhuman manner." Whether any of the feisty Palatines involved in this brawl ever made it to colonial New York is uncertain, but those who did most certainly possessed a similar fighting spirit.[5]

By late 1709, the British government realized that the Germans had to be dispersed to alleviate mounting tensions in London. As Simmendinger noted, the Crown sent approximately 1,000 unfortunate souls back to Rotterdam and, eventually, on to Germany. Some of their more fortunate counterparts settled in England and Ireland, whereas others set sail for the English plantations in Jamaica, the West Indies, and the American colonies. Approximately 650 Germans settled near Bath, North Carolina, where they joined the Swiss settlement established by Christoph Baron von Graffenreid, but most immigrated to the middle Atlantic colonies.[6]

A quarter of the Palatines who sojourned in London went to New York under a plan devised by the Earl of Sunderland and endorsed by Governor-Elect Robert Hunter (fig. 6). They envisioned Protestant settlements that would serve as a bulwark against French encroachment and as a source for naval stores manufactured from the native pines of the Hudson River Valley. The Palatines agreed to remain in the service of the Crown until they repaid all the expenses incurred for their transportation and settlement, and the British government agreed to give each settler forty acres free from taxes and quit rents for seven years once payment had been made.[7]

The Palatines bound for New York boarded eleven ships in December 1709 but did not leave port until the following April. Nearly a fifth died in passage owing to their unhealthy diet and the spread of typhus. Upon their arrival that summer, the Palatines established a camp at Nutten (Governor's Island) in New York's harbor, a safe distance from the general populace which was anxious over the arrival of 2,000 diseased immigrants. To achieve the goals underlying the Earl of Sunderland's plan, Governor Hunter purchased 6,000 acres on the east side of the Hudson from Robert Livingston (figs. 7, 8), Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Simmendinger noted:

Since we were all in duty bound to live upon the grace of the Queen and under her services, we camped for a time near the City of New York, until, away from there, and about fifteen miles south of Mr. Livingston's tract, we began to erect cabins, which everyone fashioned according to his own invention and architecture. During this time--because it was planned to seize Canada or New France...whose inhabitants were mostly savages--equipment, bread and other necessities of life were provided for us, but as the campaign did not succeed as expected, after our return march certain work which consisted in the burning of tar was demanded of us, which was carried on with much labor for two years, yet with no special and evident profit to the Governor. Thereupon each received his freedoms to the extent that he might seek his own piece of bread in his own way within the Province until the Queen should again need our services and we, prepared for the first call, could be assembled together. I, for my part, returned once more to the aforesaid New York, lived about four years on the long island, a half hour distant, and in the village of Brooklyn situated there, and sought sustenance by various labors among honest people.[8]

Although enlightening, Simmendinger's account hardly describes the wretched existence of the Palatines' first years in the Hudson Valley or the Crown's ineptitude in helping them produce naval stores. In selling Hunter a portion of his land, Livingston sought to promote growth in and around his manor. Prior to the sale, he shrewdly arranged to have himself appointed as the colony's inspector of the Palatines and procured the contract for providing them with bread and beer. Despite his well-laid plans, Livingston had problems from the start. Because he was unable to get enough grain to make sufficient quantities of bread and beer, the Palatines nearly starved the first winter. The colonial government's failure to provide an experienced manager to supervise the production of naval stores exacerbated the problems at East Camp. By the spring of 1711, some of the Palatines were planning to escape to Schoharie, west of Albany (fig. 8). The leaders of this small clandestine group were under the mistaken impression that the Queen had acquired land for them there from the Indians. A concerned Robert Livingston appealed to Governor Hunter for help in dealing with the Palatines. Hunter visited East Camp and tried to rally the Germans to their assigned task but was unsuccessful and subsequently intervened with the militia. Shortly thereafter, Hunter admitted that the effort to produce naval stores was a failure and terminated the program.[9]

Although their settlement was in shambles, the Palatines had fulfilled their obligations to the Crown by 1712. Some became tenants on Livingston's manor or remained as squatters on the original tract known today as Germantown, but nearly half moved to the New York City vicinity, the Schoharie Valley, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania the following year. Many of the Germans remained together after leaving East Camp. Those who moved south to the Beekman Patent in northern Dutchess County established the settlement of Rhinebeck.

One of the schränke (see fig. 4) reportedly descended in the female line of Palatine families from Rhinebeck, most recently the Travers. The other schränk (see fig. 3) probably belonged to a first-generation German settler in the vicinity of Rhinebeck, Germantown, or Livingston Manor. Dr. John Paul Remensnyder of Saugerties, New York, who donated the piece to the Ulster County Historical Society, stated that he purchased the schränk on the "other side of the River," presumably in southern Columbia County or northern Dutchess County.[10]

The Remensnyder schränk (fig. 3) has traditionally been mistaken for a kast, a Netherlandish cupboard form common in the Hudson Valley. It and the nearly identical Traver family example provide a unique opportunity to examine the work of an early Palatine joiner. Formal analysis of these two objects may facilitate the identification of other furniture made by members of this largely forgotten cultural group and illuminate their contributions to early New York material culture.

Like kasten in Netherlandish households (fig. 9), schränke (fig. 10) were the principal forms for storing textiles and clothing in the Teutonic countries from the late Renaissance until the late eighteenth century. The Remensnyder schränk is a type known in Germany as a kleiderschränk (clothing cupboard). This form typically has an interior arrangement consisting of an open area with pegs for hanging clothes in one half, and a shelved section for storing folded garments or textiles in the other (fig. 11). The Traver schränk differs in having a single compartment with full-width shelves like New York kasten (fig. 12). This arrangement was designed for the storage of bed linens, tablecloths, and other textiles associated with the dowries or outsets that women brought to their marriages. German examples fitted in this manner are referred to as wäscheschränke, or linen cupboards. No New York kast with a kleiderschränk interior is known, and Pennsylvania German schränke with wäscheschränk arrangements are rare. The interior of the Traver family schränk may reflect acculturation on the part of the Palatines into the Hudson River Valley's predominantly Dutch culture.

If the dates assigned to the New York schränke are accurate, as their style, construction, and workmanship suggests, they are the products of a first-generation Palatine joiner and document the direct transfer of southern German baroque design. The urban antecedent for these objects is the Frankfurt nasenschränk or "nose cupboard" (fig. 10). The latter term derives from the proboscis-like knobs at the tops and bottoms of the quirk moldings on the front corners, which on this baroque behemoth are nearly as large as organ pipes. Made for farming families in provincial settings, the Traver and Remensnyder schränke are simpler evocations of this sophisticated and visually complex urban form. They aspire to the grandeur of their high-style counterparts in several ways. Both have enormous, dynamically curved cyma base moldings, which unlike those on the nasenschränk, are fitted with drawers at the front. The quirk moldings on the corners of New York schränke are minuscule versions of those on Frankfurt examples, but they clearly reference the same baroque detail. To simulate the opulent visual effect of exotic veneers, which are common on urban German schränke, the New York joiner used pigmented varnishes. Remnants of what appears to be stylized rosewood graining remain on the cornice of the Remensnyder schränk (fig. 3). The Traver family example has a faux curly maple surface over an original varnish that may have been grained like that of the Remensnyder schränk.[11]

The construction of the New York schränke also relates to early eighteenth-century German work. Both pieces have locking systems (figs. 13, 14) that secure the cornice and base to the center section and allow the schränke to be disassembled and moved more easily from place to place. Other Germanic details are the wooden pins (pegs) securing the thick pine bottoms of the drawers (fig. 15) and wedged dovetail joints of the drawer frames (fig. 16). The joiner also drove a wedge into the tenon of each foot piercing the bottom of the case.[12]

Like most New York kasten, the Remensnyder and Traver schränke have massive cornices. The cornices on the kasten are comprised of a single, wide molded board angled to extend out at the top, whereas those on the schränke are comprised of several narrow molded boards. One similarity between the moldings on the schränke and kasten from the Elting-Beekman shops that flourished in the vicinity of Kingston, just across the Hudson River from Rhinebeck, is the use of splines to reinforce the miter joints (figs. 17, 18). The joiner responsible for the schränke also used them to help prevent the large miters of the base section from separating (figs. 19, 20). Kingston kasten (see fig. 12) usually have only one spline at the very top of the cornice because the front and side molding are comprised of a single board, whereas the New York schränke have multiple splines. The use of splines on Ulster County kasten is difficult to explain, since similar forms from other areas of New York do not have them. It is possible that a Palatine journeyman introduced them to the Elting-Beekman tradition. Although one hesitates to ascribe too much influence to Germanic joiners during the early 1700s, the impact of one or two individuals cannot be discounted, particularly in rural areas where furniture makers were relatively scarce.[13]

Not surprisingly, only a few artisans can be identified as possible makers of the shränke. A house carpenter could have made the pieces, but their complex construction is much more typical of a furniture joiner. One of the most intriguing candidates is joiner Melchior Gülch (also referred to as Gilles or Hilg), who arrived in New York in 1708 and subsequently settled at Newburgh, about twenty miles south of Rhinebeck on the west side of the Hudson. When the Kocherthal party sailed for New York in October 1708, Gülch and his family had stayed behind because his wife was sick with "a cancer of the breast." Frau Gülch soon succumbed to the illness, and Melchior petitioned for transportation to New York the following April. His arrival caused some dissention when he landed at Newburgh with his children Magdelena and Heinrich, who were about twelve and ten years old respectively. Although Gülch was the only joiner in Kocherthal's party, the settlers at Newburgh claimed his tools by common division. On April 29, 1710, Gülch sought to block the division. His petition stated that the tools were a gift intended for use by him, his son, and his apprentice. The latter may have been Isaac Türck, the only single man in the Kocherthal party. Either Türck or young Heinrich Gülch are also possible makers of the schränke.[14]

The elder Gülch was clearly a well-established resident of Ulster County by 1717, when he appeared as "Gullis, the German joiner" in a list of land grants. Two years earlier a man described as "Melgert the joyner," perhaps the same individual, lived in the precinct of Highland on the west bank of the Hudson River just opposite Poughkeepsie in Dutchess County. If either of these men was Melchior Gülch, he moved closer to Rhinebeck and Kingston at an early date.[15]

The English Board of Trade's lists of "poor Germans lately come over from the Palatinate into the kingdom" taken at St. Catherines, Walworth, and Debtford in May and June of 1709 simplifies the process of identifying and locating Palatine tradesmen who immigrated to New York. These documents provide detailed demographic information on the first 6,000 Palatines who arrived in England earlier that year. Of the 1,232 adult males included in the total, only twenty-one were described as joiners, and only two appear on later government lists as New York immigrants: Peter Dinant, aged thirty-nine in 1709, and Peter Pfuhl, aged forty-eight. Dinant's household included seven family members prior to his departure, but only four survived the journey to New York. His daughter Susanna was baptized at the Kingston Reformed Church on October 28, 1711. Although nothing is known about Dinant's career as a joiner, he must also be considered a candidate for the maker of the Traver and Remensnyder schränke. His church affiliation in Kingston might indicate that he lived there and had contact with tradesmen in the Elting-Beekman shops.[16]

Born in Nider-Rammstadt in Darmstadt, Peter Pfuhl married widow Anna Sophia in the West Camp Lutheran Church in Ulster County north of Kingston on September 27, 1710. He was still at West Camp on April 19, 1713, when his daughter Anna Catharina was baptized in the same church. By 1716, he had moved to Raritan, New Jersey, on Newark Bay. The New York City Lutheran Church Book documents the baptism of three of Pfuhl's children between 1716 and 1721.[17]

Although joiners were undoubtedly among the approximately 7,000 Germans not included in the Board of Trade's initial lists, it is doubtful that many more furniture makers immigrated to New York and worked in the Hudson River Valley. Given the fact that Pfuhl only resided in the Kingston vicinity between 1710 and 1716, one of the Gülchs, Melchior's apprentice, or Peter Dinant become the most likely candidates for maker of the Traver and Remensnyder schränke.

The massive wäscheschränk illustrated in figure 21 may also represent the work of a Palatine joiner. Its early German baroque design and gum secondary wood points to New York as the probable place of origin. Like many late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century schränke from the Rhine River port Mainz and other parts of Germany (see fig. 22), the example shown in figure 21 has doors with complex applied moldings (fig. 23). The joiner used a scratch-stock cutter to produce the moldings, which must have been an arduous task considering their size and profile. This may indicate a production date before 1720, when dedicated molding planes of this size became more widely available. The dramatic geometry of the moldings may have been derived from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century fortress plans.[18]

No other American wäscheschränk like the one illustrated in figure 21 is known. Its drawer construction (fig. 24) is fairly typical of New York baroque cabinetwork, but the dovetails at the corners of the frames are not wedged and the bottoms are not pinned as one might expect on such an overt Germanic form. The large cornice is comprised of multiple parts as on the Traver and Remensnyder schränke, but there are no splines reinforcing the miters. One unusual feature of the cornice is its blind-dovetailed frame, which forms the fascia just below the uppermost cyma recta. This detail does not occur on any other seventeenth- or eighteenth-century New York case pieces, and could, if discovered in other furniture, help establish a link between the wäscheschränk and related work by Germanic (or Anglo) artisans in New York and other colonies such as Pennsylvania.

The quality and sophistication of the wäscheschränk's construction far exceeds that of the Traver and Remensnyder schränke, and appears to represent a different German tradition. The maker of the wäscheschränk was undoubtedly a joiner or cabinetmaker whose patrons were upper middle class burghers and merchants, whereas the joiner responsible for the Hudson Valley schränke probably produced furniture and architectural components for a predominantly rural clientele. The latter class of patrons had neither the means, nor necessarily the desire, to fill their homes with furniture in the latest style.

The workmanship in the upriver schränke is charmingly direct, if not somewhat coarse, as evidenced by their maker's failure to scrape away the marks left from the hollow and round planes he used to form the large, ogee-curved bases and the Welded door panels. The joiner may have assumed that surface irregularities would be concealed by the grain-painted decoration. Given the fact that painted pine dower chests are the only other Palatine case forms found in New York, it is possible that most of the German joiners who immigrated were from a class of furniture makers similar to the witwerkers of the Netherlands. These artisans specialized in the production of relatively simple forms made of soft, light-colored woods that were invariably painted. The joiner who made the Traver and Remensnyder schränke used maple for the primary wood. This would have been a logical choice for a rural Germanic witwerker who wanted to add durability to two ambitious forms.[19]

In contrast, the sophisticated style and construction of the New York wäscheschränk suggest that its maker worked in a large town or urban area. Joiner Christian Hartman, who is listed as a freeman in 1715, is the only Germanic furniture maker documented in New York City during the dates assigned to this imposing form. Unfortunately, his name does not appear in the lists of Palatines prepared by the Board of Trade, the Hunter Subsistence Lists, or in the Simmendinger Register. Other Hartmans are recorded, however, including a Johann Hermann and a Peter. A "master Chrisitan Hartman, citizen and carpenter" appears in an early reference in a Frankfurt churchbook. He was a sponsor of the baptism of Anna Elizabeth Bergman (b. 1707), whose parents Andreas and Anna Sibylla immigrated to New York with other Palatines in 1709. Regrettably, it is impossible to determine if he is the same Christian Hartman who worked in New York City.[20]

One can only speculate about the work of urban Palatine joiners such as Christian Hartman, but it is probably safe to assume that they had to adjust their styles to accommodate prevailing New York tastes and cabinetmaking traditions, which turned increasingly to London by the mid-eighteenth century. With their tulip poplar sides, competent dovetailing,and lipped fronts, the drawers of the wäscheschränk differ little from those in other New York baroque case forms. The acculturation of immigrant artisans probably occurred more rapidly in the cosmopolitan environs of New York City than in the rural Hudson River Valley. But even in the latter region, interaction with artisans with Dutch, French, and English backgrounds, intermarriage with people from other ethnic groups, and the contingencies of frontier life probably helped transform the furniture making traditions of the few Palatine German joiners who survived the debacle on Livingston Manor. The products of these artisans represent another of the myriad ingredients that make New York baroque furniture such an appetizing stew.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author thanks Luke Beckerdite for suggesting that he publish these New York schränke, and Gavin Ashworth for his superb photography. Others who have helped in the preparation of this article include Roderic Blackburn, Dennis Bakoledis, Dean Failey, Amanda Jones, Neil and Madeline Kamil, Nancy Kelly, Noe Kidder, Wolfram Koeppe, Leslie Lafever-Stratton, Jack Lindsay, Mr. and Mrs. Henry Livingston, William E. Lohrman, Kim Orcutt, Steve Regan, Donna Reston, John Scherer, and Alvin Sheffer.

The area known to the English-speaking world as the Palatinate is referred to as the Pfalz in Germany. Geographically the Palatinate comprises two regions of Germany, the Rhenish or Lower Palatinate (Ger. Rheinpfalz or Niederpfalz) and the Upper Palatinate (Ger. Oberpfalz). The Rhenish Palatinate extends from the left bank of the Rhine and borders in the south on France and in the west on Saarland and Luxembourg. Traditionally, it has been an agricultural area, famed for its wines, and the majority of the Palatines who came to New York were from this geographic region. The Upper Palatinate is a district of northeast Bavaria on the right bank of the Rhine, separated in the east from Czechoslovakia by the Bohemian Forest. The name of the two regions came from the office known as count palatine, a title used in the Roman, Byzantine, and Holy Roman empires and elsewhere, notably in England, Hungary, and Poland (The New Columbia Encyclopedia [New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1975]). The only other published works on New York Palatine furniture are by Mary Antoine de Julio, whose research focuses on painted chests. See Mary Antoine de Julio, German Folk Arts of New York State (Albany, N.Y.: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1985), pp. 3-17; and Mary Antoine de Julio, "New York German Painted Chests," Antiques 127, no. 5 (May 1985): 1156-1165. In her essay and article de Julio provides the name of only one possible maker, a Johannes Kniskern, who by family tradition is said to have made identical chests for his twin daughters. She does not present conclusive evidence, however, that Kniskern was a joiner.

Ulrich Simmendinger, Warhoffte und glaubwürdige Verzeichnüss jeniger Personen; welche sich ano 1709 aus Teutschland in Americam oder neue welt begeben, translated by Herman Vesper (1717; reprint, St. Johnsville, N.Y.: L. D. Macfiethy, 1934), p. vii. The "golden promise of the English letters" probably refers to the so-called "Golden Book" which the British government circulated throughout southern Germany before 1709. This book depicted British North America as the promised land. For more on the "Golden Book" see Jones, The Palatine Families of New York, 1: iv.

Ruth Piwonka, A Portrait of Livingston Manor 1686-1850 (New York: Friends of Clermont, 1986), pp. 30-33; and Jones, The Palatine Families of New York, 1: xiii-xvi. A smaller number of Palatines involved in the naval stores project settled directly across the Hudson from Livingston Manor at a place called West Camp. Some of these West Camp settlers moved back across the Hudson onto the Beekman Patent when the project collapsed and settled in and around Rhinebeck with their fellow countrymen from East Camp.

The author thanks William E. Lohrman and Steve Regan for bringing the schränk illustrated in fig. 4 to his attention, and Dennis Bakoledis for information pertaining to its history (Dennis Bakoledis to Peter Kenny, February 15, 2000.) The author also thanks Nancy Kelly of Rhinebeck, New York, who interviewed Mrs. Ada Harrison, whose sister Muriel Goodwill and brother-in-law Harold Goodwill consigned the schränk for auction in 1995. According to Mrs. Harrison, the schränk belonged to her grandparents, William Rynders and Samantha Traver. Samantha was the daughter of Stephen L. Traver. Mrs. Harrison told Mrs. Kelly that the schränk was a marriage gift to daughters in her family. If this tradition is correct, Samantha would have received the schränk from her mother Rosina Mead Traver (1826-1902). Rosina's mother was Elizabeth Pink Mead (m. 1804), who may have inherited the schränk from her mother Catharina Holsapple. Given the probable date of the schränk, it may have originally belonged to Susanna Link who was born at Livingston Manor on February 27, 1734, or her mother. This genealogical information is derived from inscriptions in a bible owned by Mrs. Ada Harrison. Conversation between the author and Amanda Jones, Director, Ulster County Historical Society, Marbletown, New York, April 10, 2000.

Nathaniel B. Sylvester, History of Ulster County, New York (Philadelphia: Everts and Peck, 1880), p. 30. The History of Ulster County, New York, edited by Alphonso T. Clearwater (Kingston, N.Y.: W. J. Van Deusen, 1907), p. 71.

The English Board of Trade Lists of 1709 are reprinted in New York Genealogical and Biographical Records, vol. 40 (1909), 49-54, 93-100, 160-67, 241-48 and vol. 41 (1910), 10-19. In addition to the twenty-one joiners, ninety carpenters are listed. Although carpenters often made case furniture, the sophisticated style and construction of the schränke suggest that they are the products of furniture joiners. Accordingly, only members of the latter trade have been researched in the course of this study. The men who compiled the lists for the British government understood the distinction between the two trades. For more on Dinant, see Jones, The Palatine Families of New York, 1: 171.

For witwerkers, see T.H. Lunsingh Scheurleer, "The Dutch and Their Homes in the Seventeenth Century" in Arts of the Anglo-American Community in the Seventeenth Century, edited by Ian M. G. Quimby (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974), pp. 14-15. Scheurleer states that the witwerkers became part of the Josefs Guild of furniture makers in Amsterdam in the late seventeenth century. According to him many artisans came to Amsterdam from Belgium and Germany in the seventeenth century and were incorporated into the Josefs Guild.